THE DEATH OF IVERSON'S BRIGADE

by Gerard A. Patterson

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

He is an associate editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and a member of its editorial board. He resides in Mt. Lebanon, Pa., with his wife, Diane. They have two sons, Eric and Marc.

One-hundred yards now, at most, the Southerners on the right, even closer, close enough for the hidden Union troops to see the names of their battles stitched on their red banners-the Seven Days, Sharpsburg, South Mountain, Chancellorsville - a veteran unit for certain. Those troops on the left, they observed, seemed to be drifting somewhat away from the other three regiments. If there was anyone in overall charge of the brigade to correct the alignment, it was not apparent.

At eighty yards came the shouts, "Fire, fire, fire"' The Union soldiers sprang to their feet in front of the startled Rebs who-with no skirmish line in front of them to detect the hidden force-stopped in their tracks, suddenly aware of their utter defenselessness in the open field.

The first volleys from the Yankees in front of them and, even more devastating, from those enfilading their exposed left flank where the stone wall abruptly turned to follow the road, killed or wounded nearly five-hundred men, dropping them in an even, seemingly endless row. Those not hit, hugged the ground, crawling into a muddy recess in the field that afforded no other protection from the Union riflemen.

In just a few minutes on this first day at Gettysburg, Iverson's Brigade, Robert E. Rodes' Division, Second Corps, Army of Northern Virginia, would be virtually annihilated, the remnants signalling surrender by slowly waving their slouched hats, or dangling pieces of their shirts that they had ripped away. Only five of Gen. Robert E. Lee's thirty-seven infantry brigades would return from the disastrous Pennsylvania campaign with longer casualty lists. What had happened? How could one of the most battle- seasoned units in the army have been caught in such a trap? Who was responsible? The answers form a tragic story of one of the most flagrant cases of irresponsibility and bungling, if not outright cowardice, by a commander to which any unit, blue or gray, was subjected during the war.

The trauma that Brig. Gen. Alfred Iverson's men-the 5th, 12th, 20th, and 23d North Carolina regiments-would experience that afternoon was intensified by the fact that only the day before, they had been enjoying a relaxing time at Carlisle Barracks, the historic post twenty-five miles away where many of their leaders, including Iverson, had been stationed before the war when they were in the U. S. Army.

While their commanders renewed social acquaintances in the area, the men were left much to themselves to rest after their arduous advance through the Shenandoah Valley and Pennsylvania. Their only tasks were to help confiscate saddles, bridles, medicines, and other supplies needed by the army. In fact, Iverson and the men of the four other brigades of Robert E. Rodes' division, had had it a bit too easy during the three days they spent in the town. Caches of hard liquor were discovered under haystacks and in other hideaways. A member of the Twenty-third North Carolina admitted "many of our jaded, weary boys drank too much U. S. Govt. whisky and a battle with a Georgia regiment for the time likewise drowning their weariness was narrowly averted." Ice appeared to be just as readily available and "mint juleps in tin cans were plentiful," said another Tarheel.1

The high officers of the division behaved little better. An aide to General Rodes had found a keg of lager beer and, by the time they were to take part in a flag raising ceremony at the barracks, the usually stern Rodes and his staff were all "somewhat affected by liquor," Maj. Campbell Brown noted in his journal. One subaltern was so inebriated he had to be dragged away when he tried to give a speech.2

"The beer was the strongest I ever saw, I must admit by way of excuse, probably mixed with whiskey," Major Brown added and made it plain that "I never saw Rodes intoxicated before or since.'; There had been so much hell- raising during the prolonged stay, that a Carolinian who had taken part later was convinced that "one of the main causes why we lost Gettysburg was liquor."3

The party ended when Rodes' division was abruptly ordered to proceed to Cashtown, or Gettysburg, to consolidate with A. P. Hill's Third Corps. Although they had hoped to move farther north and capture Harrisburg, only twenty miles away, the Confederates reversed their course and, with heads throbbing from their revelry, shuffled off.

The division bivouacked that night at Heidlersburg and, in the morning, resumed its march. The troops had reached a point about four miles from Gettysburg, when the distant rumble of cannon and musketry told them of the storm they were approaching. The division commander went ahead to reconnoiter and saw the Confederate Third Corps engaged on McPherson's Ridge and bluecoats streaming through the town to extend their lines at a right angle to their existing position.4

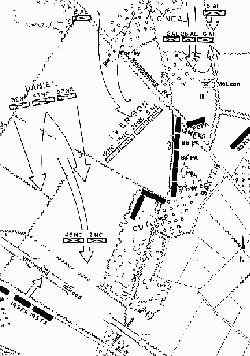

"To get at those troops properly," Rodes explained later, he moved his brigades off the Heidlersburg road and along wooded Oak Hill to a point he thought put them on the flank of the Union First Corps. He directed General Iverson and Col. Edward O'Neal, in command of an Alabama brigade, to advance down the slope while he held the North Carolina brigades of Brig. Gens. Junius Daniel and Stephen Dodson Ramseur in reserve, and the Georgia troops of Brig. Gen. George Doles in a defensive stance.,"5

Based on what was known of General Iverson at that time, Rodes could hardly have made a better choice of a man to lead his attack. Son of a prominent U. S. Senator from Georgia, Iverson, though only thirty-four at Gettysburg, had seen service in the Mexican War as a seventeen-year-old youth, dropping out of a Tuskegee, Alabama, military school joining his father's regiment to cross the Rio Grande.6

Afterwards, Iverson tried studying law and railroad contracting, but it was the military that interested him. Through his father's influence with his Washington friend, the then Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis, young Iverson received a commission as a first lieutenant with the U. S. First Cavalry, a rare honor for someone not graduated from West Point. Few saw more action in such a brief time. Iverson went from service against the Border Ruffians in Kansas and Nebraska, to the expedition against the Mormons in Utah, and then campaigns against the Comanches and Kiowas, so that when the Civil War began he was a seasoned army officer, albeit not formally educated.7

At the outset of the war, Iverson organized several volunteer companies into the Twentieth North Carolina Regiment and led that unit through the Seven Days, during which he was severely wounded. He later distinguished himself during the Antietam Campaign.8

Iverson's service in the Confederacy had been so extraordinary that, when questioned later about his promotion to brigadier, which came in November 1862, President Davis was quick to defend his action by pointing out that Daniel Harvey Hill, a very tough man to please, had recommended Iverson by referring to him as "in my opinion, the best qualified by education, courage and character of any colonel in the service for the appointment of brigadier general."9

It was Lt. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson who, when presented with a group of five colonels being considered for advancement, advised that "Iverson be the first promoted" and Lee, himself, who forwarded the endorsement, marked it for "favorable consideration."11

In reference to Iverson's early election as colonel of the Twentieth North Carolina, Davis reminded Governor Zebuton Vance, when pressed, that "it was not I who placed this gallant son of Georgia in command of North Carolina troops but that a regiment of your state adopted him, selected him for its colonel and was commanded by him on many bloody fields. I had every reason to believe that he was recognized with pride by North Carolina generals and soldiers who had witnessed his bearing in battle."11

Less than two months before Gettysburg, Iverson had had an experience at Chancellorsville that may have influenced his subsequent behavior, even more than the heavy drinking that went on at Carlisle. That was when he, as he put it, "received a contusion in the groin from a spent ball which makes walking very painful."12 Such an incident might make any man a bit gun shy. But in placing him in the van, General Rodes had, until then, little reason to doubt that he was leading with one of his most tried and tested commanders, far more so than Daniel, new to the army, or even Ramseur, who had missed all the battles from Malvern Hill to Chancellorsville because of wounds.13

What would happen to Iverson's brigade when it crossed the Forney fields actually was predetermined while it was still forming for the advance. On the left, O'Neal's men Yankee force strung along the Mummasburg Road, and were quickly turned back. This decisive repulse had left two Union regiments that had done the damage, free to do an about-face and advance, under cover of woods, to the low stone wall behind the units so that they could face the left flank of Iverson's Brigade, fully exposed, as it advanced in its diagonal course.14

There was little chance that the bluecoats would be discovered, because Iverson - in his first grievous mistake of the day-had neglected to send skirmishers ahead of his line to detect such traps.

Just what was Iverson doing to guide his troops? Precious little, the evidence indicates. "lverson's part in the heroic struggle of his brigade seems to have begun and ended with the order to move forward and give them hell," said Capt. Vines E. Turner of the Twenty-third North Carolina. "After ordering us forward," Turner wrote, the brigade commander "did not follow us in that advance and our alignment soon became false." Moreover, "there seems to have been utter ignorance of the force crouching behind the stone wall."15

Lt. Walter A. Montgomery of the Twelfth North Carolina, concurred. "lverson's men were uselessly sacrificed. The enemy's position was not known to the troops. The alignment of the brigade was a false alignment and the men were left to die without help or guidance."16

That Iverson, himself, was nowhere to be seen was confirmed by a chorus of Carolinians. A committee of survivors of the Twentieth North Carolina recorded that "the brigade commander, General Iverson, did not go into the battle." The way Pvt. J. D. Hufham Jr., of Ramseur's Brigade, heard it, "General Ivison (sic), who was drunk, I think, and a coward besides, was off hiding somewhere." Lt. Col. William S. Davis of the Twelfth North Carolina, remembered being "left alone without any orders, our general in the rear and never coming up."17

Another chronicler said "Iverson was seen no more after his line crossed the Mummasburg Road. Rumor had it that he not only remained in the rear but that a big chestnut log intervened between him and the battle and that more than once he reminded his staff that for more than one at the time to look over was an unnecessary exposure of person."18

Iverson's absence was felt more intensely because of the fact that only one of his regiments, the Twenty-third North Carolina, was being led that day by a full colonel-Col. Daniel H. Christie, the thirty-year-old founder and superintendent of a Henderson, North Carolina, military school. The Fifth North Carolina was going in under a captain, Speight B. West. All the other regular regimental commanders were absent wounded, Chancellorsville having taken a particularly heavy toll of officers.19

The Federal troops Iverson's men encountered consisted of a mixed brigade of regiments from New York, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts belonging to the First Corps. It was commanded by a fiercely-bearded, forty-one-year-old miller-turned-soldier from Michigan, named Henry Baxter. As a young man, Baxter had joined the gold rush to California and spent three years panning in the fields before giving up and returning home. He was ready to show both his tenacity and daring again that day.20

Baxter had marched his men from Emmitsburg that morning, arriving on Seminary Ridge just after John F. Reynolds, the corps commander, had been killed and the Confederate Third Corps assault blunted.

When he reported to Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday, the acting corps commander, Baxter was ordered to help extend the Union right across the Chambersburg road and beyond the unfinished railroad cut, where heavy fighting had already taken place. Taking advantage of the woods behind the wall bordering the Forney farm, he was able to move his men into position along Oak Ridge without the Rebs seeing how the Union line had been prolonged, and it was he who had confronted O'Neal with his right regiments and then quickly turned them around to face Iverson's flank .21

Pvt. John D. Vautier of the Eighty-eighth Pennsylvania said later that the brigade had gotten into place "none too soon, for the field in front was swarming with Confederates, who came sweeping on in magnificent order, with perfect alignment, guns at right shoulder and colors to the front." Vautier said they "waited quietly for the enemy to come within range, word being passed along to aim low, and at the command a sheet of flame and smoke burst from the wall with the simultaneous crash of the rifles, flaring full in the faces of the advancing troops, the ground being quickly covered with their killed and wounded as the balls hissed and cut through the exposed line."22

"We delivered such a deadly volley at very short range that death's mission was with unerring certainty," was the grimly poetic way Lt. Col. A. J. Sellars of the Ninetieth Pennsylvania put it.23

The shock was incredible. All that Iverson's Carolinians could do was flatten themselves in the dip about eighty yards from the wall and try to form a firing line, though still fully exposed to the enfilade fire on their left. "Unable to advance, unwilling to retreat, the brigade lay down in this hollow ... and fought the best it could," Captain Turner said. Every commissioned officer of the Twenty-third North Carolina except one was shortly killed or wounded.

"I believe every man who stood up was either killed or wounded," Lt. Oliver Williams of the Twentieth North Carolina recalled. 24

From wherever he was, Iverson could see his men stretched out in a long straight line, seemingly helpless, and must have begun contemplating whether he was in his rightful place.

Private Vautier said two of his friends

being good marksmen, their balls struck in or near the opposing line, making it very lively for the "tarheelers" in the gully. A color-bearer, making himself very conspicuous by defiantly flaunting his flag in plain view, caused Evans to remark, as he brought his piece to his shoulder, "John, I will give those colors a whack." But no sooner had he spoke but there was a thud and the sergeant, slowly bringing his musket down, fell over dead.25

Iverson's men, already being decimated by the troops in their front and on their left, found themselves further tormented when Lysander Cutter's First Corps brigade, on their right, saw their predicament, executed a change in front, and lined up along the edge of the railroad cut to snipe at the enemy at long range.

Colonel Davis, commander of the Twelfth North Carolina, on the right of the brigade, saw a small bottom in a wheatfield and moved his unit away from the others into that recess and, because of the lay of the land, disappeared out of sight of the Confederate regiments, as well as the Yanks occupying a wooded, rocky bluff in front of him. "I was left alone without any orders with no communications with the right or left and with only 175 men confronting several thousand," the colonel said of his situation. "Here we remained in suspense but no orders came from any source."26

The suspense could not, did not, last long. From his place in the rear, Iverson said that when he "saw handkerchiefs raised and my line still lying down, I characterize the surrender as disgraceful" and frantically sent word to General Rodes that one of his regiments had given up en masse - something no Confederate regiment in the Army of Northern Virginia had ever done.27

"Handkerchiefs?" There was probably not a single white handkerchief in the pocket of any soldier lower than a general officer in that army of tatterdemalions. Whatever he had seen being waved was cloth of a different cut, but Iverson's panicky dispatch was enough to unsettle his commanders. The grisly fact was that those men lying down were all dead or wounded, and the ones doing the feebly signalling were the trapped survivors trying to give up. Crusty Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell, the one-legged Second Corps commander, recorded his reaction to Iverson's message: "The unfortunate mistake of Gen. Iverson at this critical juncture in sending word to Maj. Gen. Rodes that one of his regiments had raised the white flag and gone over to the enemy might have produced the most disastrous consequences. "28

When he saw the symbols of surrender being displayed the plucky Baxter sensed his opportunity and sent three regiments-the 88th Pennsylvania, 83d New York, and 97th New York-sallying forth over the wall. In a moment, they were upon the stunned and demoralized remnants of the 5th, 20th, and 23d North Carolina, using rifle-muskets as clubs or brandishing their bayonets to herd the Rebels back to their lines.29

Col. Charles Wheelock, and his Ninety-seventh New York succeeded in charging over the ground without having any killed and but few wounded, and "brought out as prisoners 213 officers and men of the 20th North Carolina with their colors," or "as many prisoners as we had men in our regiment."30

The flags of the Twenty-third North Carolina, and that of an Alabama regiment, carried by someone from O'Neal's Brigade who had joined in Iverson's advance, fell to the surge of the Eighty-eighth Pennsylvania which had attacked with empty rifle-muskets because all their ammunition had been used up in the slaughter. In all, approximately 350 of Iverson's men were rounded up in the rush.31

Simultaneous events in three sectors suddenly turned the complexion of things for the men remaining in the open field. On the far left, another division of Ewell's Second Corps, that of Jubal Early, had succeeded in caving in the hastily-formed Union right, manned by the Eleventh Corps The men of the Union First Corps could observe the collapse, and the bluecoats beginning to stream toward the town, when Rodes sent in another of his brigades, the crack troops of Dodson Ramseur, to relieve Iverson. At first, it appeared that Ramseur would follow the same route to disaster, but a couple of officers of Iverson's command risked their lives to rush back to the relief force in time to alert the young commander and he adjusted his point of attack to strike the flank of Baxter's force.32

About the same time, the isolated Colonel Davis, with the Twelfth North Carolina, made a decision. If he could not see any troops around him, perhaps the Yanks over the brow of the. hill in his front felt equally on their own and he could outfox them. Ordering his men to let out the loudest Rebel yell 175 voices could muster, he sent them over the rise in a wild advance.33

The pressure at so many points at once was too much for Baxter's line and it gave way, and the Yankees' turn to suffer came. Ironically, some of the Rebel prisoners were among the victims when the Federals began to retreat ward Pennsylvania College and the streets of the town, hotly pursued by swarms of Confederates closing in from all directions.

It fell to a mere captain, Iverson's young assistant adjutant general, D. P. Halsey, to assume command and try to restore what was left of the brigade to some semblance of an organization.34

When the battle moved away from that sector, a gruesome scene remained. Lt. George Bullock of the Twenty- third North Carolina said it was the only battle of the war in which he ever saw blood run in a rivulet, which was the way the bottom of the depression was where Iverson's men had been penned.35

A Yankee soldier attested: "Hundreds of Confederates fell under that first volley, plainly marking their line with a ghastly row of dead and wounded men whose blood trailed the course of their line with a crimson stain clearly discernable for several days after the battle until the rain washed the gory record away. "36 Captain Turner said that one private of the Twenty-third North Carolina was found dead clenching his rifle-musket with five bullet holes through his head.37

Bringing it down to very personal terms, a young member of the Fifth North Carolina's Gaston Guards wrote a letter to the mother of his friend and messmate to relate what had happened to him:

Leonodous [Leonidas) was shot between the Eye and ear and in the thigh. I think the ball that went in his head went near his brain. He did not know any thing for several hours. . . . When he was shot he was lying in a hollow in a very muddy place. All that were badly wounded and killed was shot in this same hollow. I was shot before the Regiment got to this place. Leonodous and I went into battle side by side. We promised each other if one got hurt to do all we could for him. Their [sic) is but seven in our Company. Times are verry disheartening here at Present.

True to his word, W. J. O'Daniel did all he could for his companion, setting him up under a tent on the field "with several blankets and a good oilcloth to ly [sic) on," but could get little help.38

"The citizens did not give the wounded any attention while I stayed," Private O'Daniel related. Finally, when the army was withdrawing, he had to leave his wounded friend, carrying home his pocket knife, Testament, and diary to his family.39

The Union wounded fared little better until the Confederates departed. A Union lieutenant said they were simply left "lying uncared for on the field, suffering untold agony from their festering wounds."40 Going over to the McPherson barn on the Chambersburg Pike, which had been turned into a hospital by both sides, the Yankee lieutenant said:

The most distressing cases of suffering met his sight, the barn being filled with helpless soldiers, torn and mangled, who in the heat of the fight had been carried there by their comrades and had lain since without care or attention of any kind. . . .Their lacerated limbs were frightfully swollen and, turning black, had begun to decompose. The blood flowing from gaping wounds had glued some of the sufferers to the floor.

The officer tore his own underclothes into ribbons to bandage some of the men.41

An artilleryman who had arrived on that part of the field during the night, woke up to discover

a sight which was perfectly sickening and heart rending in the extreme. It would have satiated the most blood thirsty and cruel man in God's earth. There were, in a few feet of us, by actual count, 79 North Carolinians laying dead in a straight line. I stood on their right and looked down their line. It was perfectly dressed. Three had fallen to the front, the rest had fallen backward, yet the feet of all these dead men were in a perfectly straight line. Great God! When will this horrid war stop? This regiment belonged to Iverson's brigade and had been pushed forward between two stone fences, behind which the Yanks were laying concealed. They had all evidently been killed by one volley of musketry and they had fallen in their tracks without a single struggle. These 79 North Carolinians were not the only dead on the hill, many others were scattered around and in a wheatfield at the foot of the hill were many dead blue coats. I turned from this sight with a sickened heart and tried to eat my breakfast but had to return it to my haversack untouched.42

Several of the wounded officers of Iverson's brigade, including Colonel Christie, Capt. William H. Johnston, and Capt. Charles C. Blackwall of the Twenty-third North Carolina, were taken to the house of P. W. B. Hankey, about a mile from the field where Christie, the military school headmaster, had "the surviving handful of the Twenty-third brought to the door and with much feeling assured them that he might never live to again lead them in battle but he would see that 'the imbecile Iverson never should."43

The colonel died of his wounds en route back to Winchester, but his intervention would not be necessary to rid the unit of Iverson. The absent commander re-emerged as a pathetic figure, best revealed by his own official report. "Arriving in the town and having but very few troops left," the commander wrote, "I informed Gen. Ramseur that I would attach them to his brigade and act in concert with him."44

He made time, at some point, to go over the ground where his leaderless men had fallen and declared haughtily in his report that when he "found 500 of my men lying dead and wounded in a line as straight as a dress parade I exonerated the survivors with one or two disgraceful individual exceptions." One would wonder if he included himself in the latter category.45

For the time being, Iverson was appointed provost marshal for the retreating army, and later served briefly as acting commander of a Louisiana brigade before being transferred to a cavalry command in Georgia. His departure from his old brigade was explained in many ways. "The brigade refusing to serve under him longer, he was transferred," said Colonel Davis. General Ramseur told his wife that his understanding was that Iverson was removed for misconduct at Gettysburg." One of Ewell's staff officers said plainly that Iverson was guilty of "cowardly behaviour." A group of Twentieth North Carolina veterans, writing their history together, recorded that the brigade commander, General Iverson did not go into the battle and was relieved of command."46

When the army got back to Virginia and a tally was made, General Rodes reported the brigade had suffered 130 killed, 382 wounded, and 308 missing, a total of 820 casualties among the 1,400 engaged, though many in the unit thought that count was low.47

That first night on the field, General Lee's pioneers dug four shallow pits in which the dead were buried. Lieutenant Montgomery of the Twelfth North Carolina said he returned to the field in 1898 and learned from Mr. Forney himself "that the place was then known throughout the neighborhood as the Iverson Pits and that for years after the battle there was a superstitious terror in regard to the field and that it was with difficulty that laborers could be kept at work there on the approach of night on that account."48

After Gettysburg, Iverson redeemed himself somewhat in Georgia by directing the Confederate cavalry movements that trapped George Stoneman at Sunshine Church (though Iverson was ill and in the rear during the battle in which the Union major general was captured). When the war was over, Iverson moved to Florida to become an orange grower. After a frost wiped him out, he returned to Atlanta to live with his daughter. He survived until 1911. The Iverson Chapter, Confederate Veterans, held a memorial service for him and the local newspapers lamented the passing of an old soldier who had served in the Mexican, Indian, and Civil wars, a man of unblemished record, it would seem save for that terrible lapse at Gettysburg, a lapse that only he could have explained.49